Radical Thinking

by Dougal Henshall 19 Dec 2014 03:58 NZDT

18 December 2014

Lift-off at the ISAF Sailing World Championship in Santander © Sailing Energy

Few from within the world of dinghy sailing in the UK would argue that there has not been a huge change in the sport over the last 25 years. Although the sport has evolved pretty much everywhere that dinghies are raced, the UK has developed along markedly differing lines to many of the other 'big' sailing nations. To see this effect at work, you only have to cross the Channel into Euro-land, to find yourself knee deep in 505s, OKs, Contenders and other so called 'traditional' International classes; there are even active fleets of ultra hi-tech boats like the Tornado cat and Flying Dutchman, classes that today are all too rarely seen around our shores. Here in the UK though dinghy sailing has gone its own way, with the sport receiving regular infusions of 'new' boats, that still somehow fail to address the worrying malaise of falling levels of participation within the sport.

For many years the 505, with its radical hull-shape, was the mainstay of high performance dinghy sailing in the UK, until it lost ground here during the 'skiff revolution'. Yet, with a bigger spinnaker and a great deal of high tech construction, the boat challenges the view that success today comes from being modern and skiff shaped, by seeing healthy year on year growth. Sadly most of the action now takes place outside of the UK, such as a recent World Championships in France, which attracted just a few boats short of 200 entries. The hope now is that when the 505s 'come home' to their World Championships in Weymouth in 2016, that the entry list will go even further and top the 200 mark - photo © 505 class

Maybe one of the issues is, that despite the undoubted technology that is being brought into boatbuilding, all the clever packaging cannot disguise the fact that too many of the new boats are modern evolutions, targeted at existing classes in the core club sailing scene. It is easy to look at the new boat scene and pass the observation that if Jack Holt or Bruce Kirby were designing their boats today, then they would make them look and behave in a very different manner to how they did 40, 50 or even 60 years ago. Yet, at the same time, the counter argument could well run along the lines that what is needed, is not less innovation, but more; rather than just copy what is already out there, the demand should be for radical thinking that will bring new designs to the market. Crucially, these must be boats that are a step function forward, rather than just a bland makeover of boats that are still major players in the sailing scene. That this lack of exciting and new thinking should be afflicting the UK is a sad reflection of a past, which saw some of the greatest innovators and designers the sport has ever seen active at sailing clubs here. The recent article in this series that looked at Austin Farrar, Peter Milne and Jack Chippendale just touched on the subject. Those three could equally have been replaced by names on a far bigger list that would include Jo Richards, Phil Morrison, Ian Holt, Nigel Waller and Mervyn Cook.

Radical innovation can sometimes bring the designer into conflict with the rule book. Despite popular thinking, there is no such thing as the 'spirit of the rules'. Development such as this, David Thomas's radically clever exploitation of a loophole in the Merlin Rocket rules, could have resulted in a smooth skinned hull and will almost always result in controversy. (The loophole in the Rules was simple: With the Merlin Rocket hull at that time being laid up from ply planks, the builder was allowed to fair these in together at the bow. But, the Rule did not stipulate how far aft the fairing could be taken. So, under the Rules, as they stood then, it would have been perfectly legal to carry the fairing in right the way aft to the transom, thus creating a smooth skinned hull) - photo © Dougal Henshall

It should come as no surprise that so many of these clever thinkers are all household names in the field of the development classes, yet it can also seem that when they step outside into a world where more commercial factors hold sway, their innovation gets tempered by the need for conformity.

A great example of this would be the Laser 5000 and to a certain extent, the Laser 4000 that followed it. Back in the very early 1990s, in its original guise as developed by Derek Clark and Phil Morrison, the boat that would later become the 5000 was as radical as anything that might have escaped from the southern hemisphere. Back then, for this sort of boat, there were few rules to break, but designer Phil Morrison still managed to escape the bounds of conventional thinking and come up with a hull shape that was a fast, yet stable enough platform for twin wiring whilst handling the huge asymmetric spinnaker in the most testing of conditions. The boat was light, stiff, and very rapid and showed every sign of being a mould breaker.

It is easy to write the Laser 5000 of as being the leaden '5-tonner', but that is to ignore the ground-breaking advance that the boat represented, both in terms of performance and racing. With high profile sponsorship from Audi, fleets competed on a Europe wide circuit, with the key events being televised. Maybe some of the skiffs that followed were better (and yes, lighter) but the fact remains that the Laser 5000 did much to show the way!

Then came the need to make this into a boat for the mass market, a high performance boat that would survive the rough and tumble of being sailed by the dinghy racing equivalent of 'the man in the street' and at the same time could be made commercially viable. The answer was to make the construction of the hull and associated equipment 'bullet proof' which they did, though in making an intended skiff into the dinghy equivalent of a brick outhouse, the legend of the '5-tonner' was born. Another part of the legend suggests that when ISAF held the performance dinghy trials at Torbole, on Lake Garda, in the autumn of 1996, the team supporting the competing 49er somehow neglected to bring along any launching trolleys. No matter, the boat was light enough to be easily lifted into the water. The old adage that weight is only of benefit in a steamroller had never been more apt; although highly rated, the 5000 would lose out to the more radical 49er.

When it first appeared, the 49er, with its lightweight hull and large sail area, was firmly positioned at the radical end of dinghy design. Yet in little more than a decade, it has moved right into the mainstream of what is now accepted as a very high performance dinghy - photo © Pedro Martinez / Martinez Studio

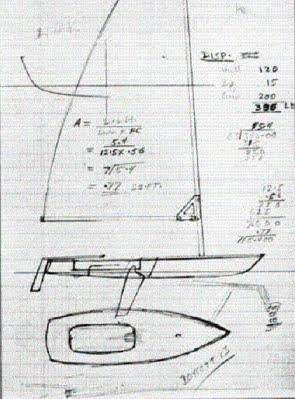

'The Million Dollar Doodle'. Late on in the swinging sixties, Bruce Kirby sketched out the idea of a new design for what was then a popular genre of boat (the 'beach' boat) and turned it into a real grown up dinghy, which was going to be called the Weekender. Was it radical? Yes, for the final version, which was by now the Laser, was clearly better than the competition, but at the same time, maybe no; Kirby had been involved the year before in the international launch for the Contender. Draw your own conclusions from that! - photo © Bruce Kirby

This then begs the question: Can both radical and commercial demands co-exist, and if so, where should it be looked for in the UK? Judging by one of the latest entrants to the single-handed market, the answer would have to be a resounding yes. Back in 2004, Dan Holman, who had been studying Ship Science with yacht and small boat design at Southampton University, was thinking about designing and building his own boat. The academic skills he was learning were being laid on top of a superb level of sailing talent, that was good enough to take him to the very edge of Olympic selection. He had been sailing in the Laser for upwards of 200 days a year, but after parking his Olympic aspirations (surely he will return to them one day!) he was casting around for a new boat. With the exception of the RS300, which he saw as a brave and progressive boat, albeit one that was a bit extreme and lacking in versatility, there was nothing else on the market that appealed. The most obvious conclusion he drew was that nobody had made a modern performance beach boat, as the existing Laser dominated that market sector.

In some ways Dan's approach could be seen as starting from a point of the utmost conventionality. Using the box dimensions of the Laser, he knew that the resulting boat would be easily car toppable, plus he would always have the Laser on hand as a performance benchmark, that he could measure his boat against. It is interesting that Dan feels that his design had more DNA from the Sunfish (the US centric beach boat, that has sold more than a quarter of a million boats) than anything else.

For many in the UK, the Sunfish is all but an 'unknown quantity', but the numbers speak for themselves. With over 250,000 boats sold, the Sunfish is still outselling the Laser. Affordable, with tight competition including a busy international scene, rigid one design rules, it is hardly surprising that the boat, which was certainly radical in its day, will continue to influence the designers of today and tomorrow - photo © Sunfish

Little wonder then, that Dan's design philosophy was for a boat truly aimed at the 21st century. Easy to transport, simple to rig, a boat that anyone could sail, but at the same time would be difficult to sail well, his boat would need to make full and intelligent use of modern materials. With his final design, Dan had arrived at a boat that would be ergonomically satisfying, to the point that the helm would feel that they were 'wearing the boat' as much as just sailing it. With the help of Jamie Stewart at Synthesize Yachts, the prototype of Dan's design would emerge as he had intended, rather than suffering the problems of other designs, where the original intention could get lost in the layup. Christened the 'Punk', the design, with its minimalistic bow sections that curve in to create a shapely hull form, the boat is, in Dan's words, "not radical but progressive, a totally fresh approach to an old and stale question". That may just be semantics, but the proof is now out in the market place, where, with input from builders Devoti, it is looking that commercial success may well have found a synergy with a more radical (or progressive) design.

Dan Holman's original design for the Punk ticked all the boxes marked 'radical' and was certainly an eye-catching boat when it debuted at the 2009 Bloody Mary. Now in the careful hands of boatbuilders Devoti, the Punk has morphed into the shapely, classy D-Zero. Along with the contemporary RS Aero range, designed by Jo Richards, these boats show just what can be achieved when world class sailors turn their hands to design - photo © Nicola Evans

By coincidence, the new Holman/Devoti single hander is ranged up against another new to the market boat from the drawing board of Jo Richards, the RS Aero. Isle of Wight based Richards has a long pedigree of clever designs going back into the glory years of the early 1970s. Like so many young designers, Jo would first make his mark in the National 12, which at that time was a hot bed of innovation. Once the class had grown away from the original clinker plank lay up, hulls could be very easily made from sheets of ply, which allowed innovation to be cheap enough to flourish, which it frequently did! It did not seem to matter that some of the innovations would push the existing rules to the limit (and sometimes beyond), the times were exciting and tailor-made for sailors and builder with fresh ideas.

Once again Jo Richards demonstrated his ability to take a conventional idea and move it up the scale towards the more exciting end of radical. With a super light weight (just how light can be seen in this picture of Jo with the boat, comfortably lifting it without strain) and easily driven hull, the RS Aero, with the largest of the 3 rigs stepped, is significantly faster than the traditional boats it will be compared against - photo © RS Sailing

Just how quickly new thinking could take effect was demonstrated one afternoon in 1978, when Jo Richards and Nigel Waller found themselves 'in funds' after an owner had been to collect his new boat. It was an opportunity to head for the nearest pub, but it was whilst Jo was stood at the bar and trying to attract the barmaid, that he folded a 'fiver' between his two forefingers and thumb. Looking at his hand, he realised that the flat piece of paper had been formed into a shape not dissimilar to the front half of a boat. After finishing their beer and maybe a few more, Jo and co-builder Nigel Waller returned to the workshop, where they started to pull a sheet of ply into the same shape as the five-pound note. There was though still the issue of the rules that covered the amount of hollow and curvature in a plank. Now conventional thinking decreed that a plank was a plank in the way that clinker boats had been made, running from stem to stern. The rules however did not go that far and just referred to 'planks'. So what if the planks started at the sheerline and ran in at an angle towards the centreline. Despite the lunchtime alcohol, the work on the new hull raced ahead, with no one wanting to stop. By midnight, the complete hull shape had been formed and the boat that would become the iconic Burton Trophy winning Punkarella was born.

An iconic picture of an iconic dinghy. Punkarella was the result of a collaboration between Jo Richards and Nigel Waller. The boat broke so many of the accepted norms (not to mention stretching a few rules along the way) and therefore perfectly fits the description of 'radical' - photo © National 12 Class

In the same year, Jo would also exercise his imagination with the first of his Merlin Rocket designs. First Meglo and then Dumper Truck started the move towards very wide and flat stern sections that offered earlier and faster planing. Like Punkarella, these boats were years ahead of their time, yet back then would come up against (and lose out to) the best of the Phil Morrison designs. A measure of how advanced Jo's thinking was can be seen in some of the very latest Merlin Rocket designs, where the trend is getting ever closer to Jo's original thinking from more than 30 years earlier.

As well as being a first rate basic trainer, the Pico has the ability to let the sailor develop more advanced skills, without the need to immediately change boats. In some ways the Pico can be seen as conventional, yet the Jo Richards flair was to take the roto-moulding process and turn a simple idea into a boat that is far cleverer than many give it the credit for - photo © Sailboats.co.uk

Yet even Jo Richards can come up against the demands of the mass market, as was shown when in the mid-1990s he penned the lines for a 'Laser Trainer'. Numerically, with over 15,000 boats sold around the world, the Pico is Jo's most successful design, yet clearly is his most conventional. That is not to denigrate the design of the Pico in anyway, for it is a very clever compromise between the stability needed in a basic trainer, and a boat that can offer more in the way of performance, that allows the developing sailor to enjoy more sailing pleasures without needing to change their boat. The Pico aside, the fertile thinking about radical design that was always ever present with Jo would resurface with the new millennium, with a design that is as radical as anything you will find in the dinghy pound.

It is hard to put the Vortex into any one category, as it is part dinghy, equally part tunnel hulled scow (with more than a passing nod to the Moths that had this layout years earlier), with some catamaran DNA in there for good measure. Jo's clever design of the Vortex would provided a stable platform for its single handed helm, then once an asymmetric spinnaker had been added, the performance of the boat was given a real turbo boost. As a design philosophy, the Vortex is very much a standalone line of thought, but unlike many of the new designs that were to surface around that time, the Vortex remains a very active class, with new boats being built to order at Brightlingsea by Rob White.

Part cat, part dinghy, with a healthy spicing of tunnel scow, the Vortex has shown how a radical dinghy can survive and prosper once it has found its own niche to occupy - photo © Vortex Class Association

Then, in 2012, Jo would show that he had lost none of his capacity for innovative and radical design, when he returned to the Merlin Rocket, with one of the very few 'all new' designs to grace the class for a decade or more. His 'Deadline' design, Superfast Jellyfish, harked back to his earlier days in the class, with a hull that is unashamedly aimed at open water performance on a Championship racecourse. Yet the undoubted abilities of the Jellyfish would run headlong into that counter argument of conservative commercialism; the availability of a winning package based around the new Winder boats is strong enough to minimise the attractiveness to potential owners of breaking ranks and 'going radical'.

Given the long term stability in terms of design within the Merlin Rocket fleet, Jo Richards showed again that he was prepared to break away from the accepted conventions of thinking with his Deadline design Superfast Jellyfish. Despite showing great promise, the harsh realities of tooling up for production have kept this initiative as a 'one–off' - photo © Richard Battery

In a way, the Merlin Rocket class are a great example of just how the wider sailing public sees the product of radical design today. For the first 45 years of the class, innovation was ever present, with ideas being trialled, some with success, others much less so.

'The Stephen Jones designed Shaft could well go down in history as the most radically designed Merlin Rocket ever. The exaggerated distortions in the hull form took the understandings of design to the limit. The hull was built by Graham Edwards in an equally radical manner, with the finished weight far lighter than other boats of the day, meaning that Shaft was full of potential, yet ultimately would be remembered as a failure - photo © Rob O'Neil

The great thing about being innovative and radical is that anyone can do it; you just have to have that ability to 'think outside the box'. Just inland from the clubhouse at Abersoch, Miles James is busy designing and building his own boats. As he is just building for himself, he is free to do as he pleases; in doing so, he is able to enjoy the freedom to push the envelope of development further than a designer who has to operate with one eye on the commercial aspect of the final boat - photo © Miles James

Then Ian Holt designed the Canterbury Tales and in the strokes of his pen at the drawing board, changed the dynamic of the class. Here was a boat that was just radical enough to offer a step function in performance at all points of the racecourse. Later on, when David Winder started the production of high quality FRP hulls to this design, the need for further radicalisation evaporated into a fleet of conformity. There are though still the odd sightings of original (and radical) thinking; Keith Callaghan penned a new design, Jo Richards and the Jellyfish and in North Wales, Miles James proved that there was still a place for the boat that is self–designed and self built.

Overwhelmingly though, the Merlin Rocket fleet was Winder-shaped, as David took the original Holt hull lines through a number of incremental development steps. But innovation and experiment never really go away as was found when reports started surfacing in online chat rooms of sightings of a strange craft being trialled out in Weymouth Bay.

Other people may have thought of a canting rig, some may have tried it, but at long last here was a practical application of the idea. No wonder that this all stemmed from a man for whom innovation is a way of life - photo © Peter Lloyd

The boat was none other than the Merlin Rocket Dark Star, the first boat to the new Genii Evolution design, a collaboration in innovative thinking between Jon Turner and Phil Morrison. In both his Merlins and International 14s, Jon had never been afraid to experiment with new ways of improving performance. In this, he was helped by the years he had spent in the Flying Dutchman class, which was at the time still the pinnacle of Olympic dinghy sailing. The demands of Olympic fame had ensured that the FD was a fertile breeding ground for new ideas (such as the spinnaker chute, which appeared first in the FD) not to mention advanced sophistication in the rig and the way it could be raked and controlled. Ever the innovator, Jon would bring ideas with him from the FD, back into the Merlin Rocket class (and others such as the Scorpion) and before long, deck stepped raking rigs had started to revolutionize the popular dinghy scene.

Now, after a number of years away from Merlin Rockets, Jon Turner was very much back and at the forefront of the move to bring innovation and radical thought back to the class. With Dark Star and then Shabazzle, the follow-up boat to the design, Jon had been able to break away from the existing conformity, with a design that balanced out an overlarge prismatic co-efficient (a measure of the respective fullness of the ends of the hull form) with a miserly wetted area. The powerful hull carries the maximum beam right to the transom, with the aft sections of the hull being given addition torsional stiffness through the inclusion of an aft buoyancy tank.

If two designers, who are both well known for their radical tendencies, decide to collaborate, it is little wonder that the result is something that fully deserves the adjective 'radical'. Another well know dinghy designer, on seeing the hull lines for the new boat from Jon Turner and Phil Morrison, commented that not only was it majorly different to the existing boats in the fleet, it was the best Merlin Rocket design he had ever seen - photo © Richard Parslow

It is not just the hull form that is benefitting from a great deal of new and innovative thought. Jon was already experimenting with the canting rig that so caught the eye at Weymouth, but in addition he tried moving the shroud positions inboard so that the boom could be released further when heading downwind. Thanks to David Winder, the class has long enjoyed 'one string' control over the rig, where, as the rake angle of the mast is altered, all the other rig settings are automatically compensated for. But for Jon, this was not really what he wanted, for he saw the 'one string system' as really a two string; one for mast forward, the other for mast back. So, once again, it was back to the drawing board, with the result being a true 'one string' operation, with a continuous control line that can be moved in either direction to control the angle of the mast. Other innovations, such as an almost frictionless barber hauler system are also being deployed. All this suggests that the charge could be laid against the Genii Evolution that it has set not only a standard for radical hull design, but at the same time, a new level of radical complexity for the one board systems.

Radical thinking can extend beyond the design of the hull and the set up of the rig. New and innovative thinking can also apply to the control lines within the boat, with clever thinking resulting in new levels of sophistication and control - photo © Louisa Archer / ABP Images

All that remains now is to see what the market makes of the new approach and if the Merlin Rocket fleet will 'buy into' the radical design or remain faithful to the tried and tested Winders. There are exciting times, not just for one class, but also for the sport in general. With the 505s voting on allowing changes that can be seen (in terms of a one design class) as radical, one can only conclude that the future will have to look different to today and that it is for the commercial aspects of dinghy design and building to catch up, rather than hold the wishes of the sailors back.